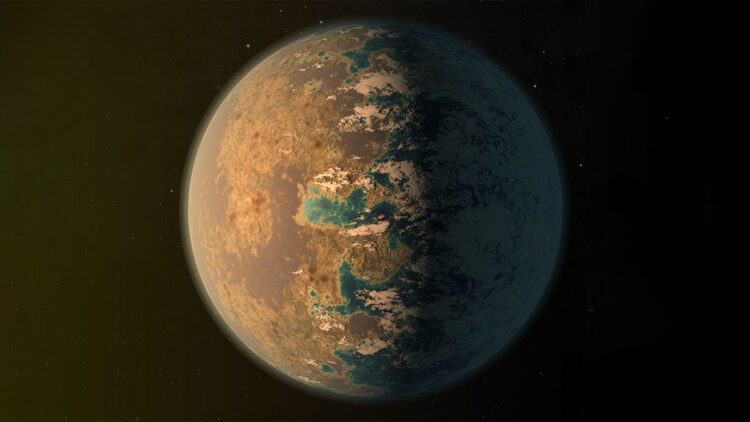

Forty light-years isn’t exactly around the corner, but in space terms it’s pretty close. The rocky planet TRAPPIST-1e is showing hints of something big: an atmosphere that could keep liquid water on the surface. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) picked up the clues by watching how the star’s light changed as the planet passed in front of it. For people who follow worlds beyond our Solar System, this is our strongest “maybe” yet.

It’s also a very human effort. Many great scientists in NASA, ESA, and CSA run Webb are working together for an analysis that runs through STScI, MIT, Johns Hopkins, and the University of St Andrews. The details are technical, but the feeling is simple: we might be seeing air around a small, rocky world.

What Webb watched for

A team led by Néstor Espinoza at STScI, with Natalie Allen at Johns Hopkins University, used JWST to watch 4 transits, those moments when TRAPPIST-1e slipped in front of its star. They searched the spectrum for tiny dips and lifts that could betray an atmosphere and, if so, what it might contain.

A second team, led by Ana Glidden at MIT, interpreted those signals. Nothing about this was easy: red dwarfs are lively, and stellar activity can smear the view, so the data needed careful cleaning before any conclusion felt safe.

As the evidence came together, one perspective stood out. “TRAPPIST-1e remains one of our most compelling habitable-zone planets, and these new results take us a step closer to knowing what kind of world it is,” says Sara Seager of MIT. “The evidence pointing away from Venus- and Mars-like atmospheres sharpens our focus on the scenarios still in play.”

Two paths, one tease

So far, the view narrows the field. The spectrum does not favor a thick, carbon-dioxide-dominated shroud like Venus or the thin, CO₂-laced air of Mars. It also seems inconsistent with a hydrogen atmosphere rich in deuterium paired with strong methane and carbon dioxide. What remains on the table is more enticing: an atmosphere dominated by molecular nitrogen with trace CO₂ and methane—one way for liquid water to stay liquid at the surface. It’s a picture, not a proof, and caution still leads.

“We are seeing two possible explanations,” says Ryan MacDonald of the University of St Andrews. “The most exciting possibility is that TRAPPIST-1e could have a so-called secondary atmosphere containing heavy gases like nitrogen. But our initial observations cannot yet rule out a bare rock with no atmosphere.” The research appears in two parts in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, and both papers carry the same careful message: Webb has given us a direction to look, not a verdict.

What’s the next step

More JWST observations are queued up to settle the question. As Ana Glidden puts it, “We are really still in the early stages of learning what kind of amazing science we can do with Webb. It’s incredible to measure the details of starlight around Earth-sized planets 40 light-years away and learn what it might be like there, if life could be possible there.”