A strange chemical fingerprint discovered deep within the seafloor could point to a nearby supernova that may have affected Earth in the geologically recent past. A German team found beryllium-10 in the Pacific Ocean in an unusual spike. This isotope is created when cosmic rays hit our atmosphere and then slowly rain down to become a part of marine crust. Since that “rain” is typically constant throughout the planet, we would expect a consistent record. Instead, the rock archive shows a distinct concentration from about 10 million years ago.

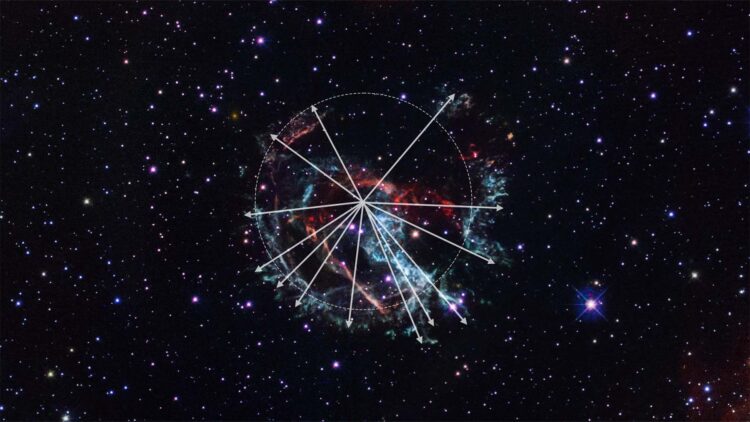

One good reason? A stellar explosion close to our solar system somewhere in the Milky Way would have exploded the particle environment and dusted our neighborhood with particles. Another team used the stars, specifically Gaia (ESA) data from the European Space Agency‘s star-mapping mission, to test this theory and estimate the probability that a star close by could have exploded around that time.

They identified clusters that might fit the timeline, so came to conclusion that these odds were actually significant. They write, “Our results support the possibility of a supernova origin for the beryllium-10 anomaly.” Although the study got published in Astronomy & Astrophysics, related research in this field frequently interacts with tools and archives from other fields as well as venues like Nature Communications.

Following a clue through time

The story of beryllium-10 starts with cosmic rays. After these high-energy particles go into the atmosphere, the beryllium-10 they produce gradually travels through the ocean and is absorbed by the seafloor. After long, long periods of time, the Pacific Ocean builds a multi-layered memory of that process. The overall consistency of beryllium-10 production should align with the seafloor’s chemical timeline. This makes the anomaly, which was centered around 10 million years ago, so interesting. Something bigger than a local blip is indicated by an unexpected, time-related spike.

The second team tested a supernova hypothesis by modeling the motion of the Sun relative to neighboring stellar neighborhoods. Using Gaia (ESA) data, they tracked the paths of 2,725 nearby star clusters and our Sun over the last 20 million years to see how many supernovae they should produce. And this showed that the probability of a star exploding within 326 light-years of the Sun was about 68% within a million years of the beryllium-10 spike.

During the same window, they also found 19 clusters with a probability of a supernova at that distance bigger than 1%. To put it another way, the proximity and timing make sense.

This is not connected with exotic mechanisms. A stellar explosion can alter the solar system’s environment and probably increase the amount of cosmic rays that reach Earth through the Milky Way’s shockwaves and interstellar dust. If a similar burst happen, we might expect a global chemical echo, which shows up in seafloor records at the same age everywhere in the world.

Should we look for a global sign?

The key test is spatial consistency. If the beryllium-10 spike is limited the Pacific Ocean regions, then, local processes could be responsible for it. Changes in ocean circulation, sedimentation rates, or the way material stick to crust can all contribute to the isotope’s regional concentration. However, if the cause was a nearby supernova, the signal should be seen worldwide at the same age. This means we would need to collect data from many different basins and closely compare ages.

The isotope progressively builds up and locks into rock over long periods of time. Some studies concentrate on layered crusts or nodules, which often include ferromanganese settings, because they can be dated and accumulate slowly. Extending the sampling grid across depths and oceans could help identifying if the anomaly is local or global.